This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The case of a Utah woman who police say was shot and killed by her ex-boyfriend shortly after getting a restraining order against him exposes gaps in the system for victims of domestic violence, advocates said Thursday.

The temporary order against James Dean Smith, 33, didn't block him from having guns, American Fork police Lt. Gregg Ludlow said. While Utah judges can order weapons taken away to protect a victim, his ex-girlfriend didn't request it and the law doesn't require it.

That's not unusual. Only a small handful of states require people to give up their weapons soon after being served with a restraining order — though that's when victims are trying to flee and abusers are likely to lash out, said Lindsay Nichols, a senior attorney with the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence in San Francisco on Thursday.

"That's really the most dangerous period of time," she said.

Smith's weapon also wouldn't have been a violation of federal laws designed to keep guns away from domestic abusers because the order against him was temporary, as is typical early in the court process.

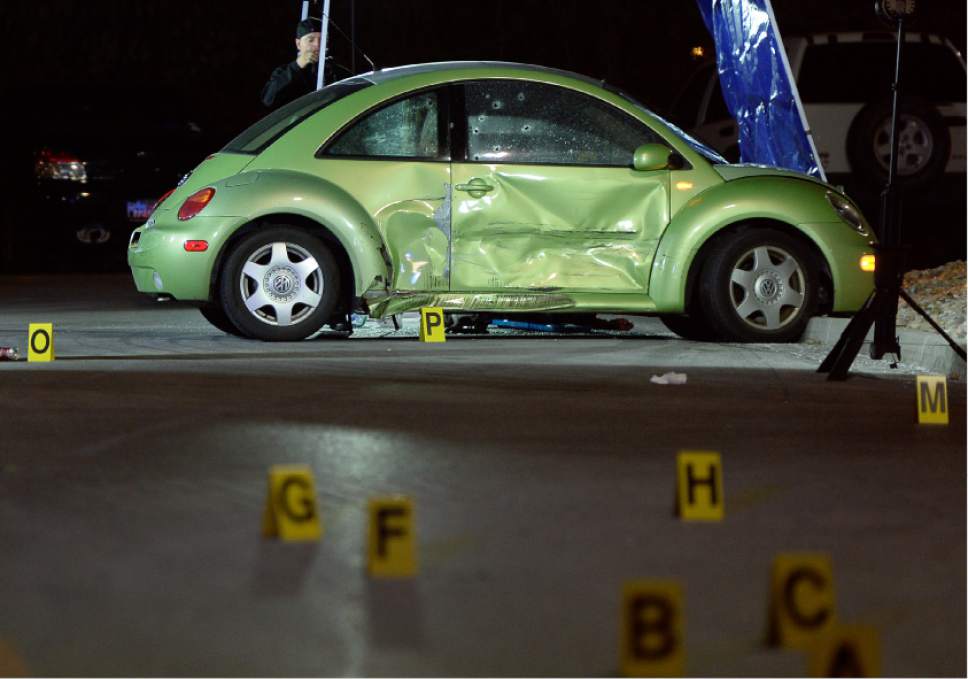

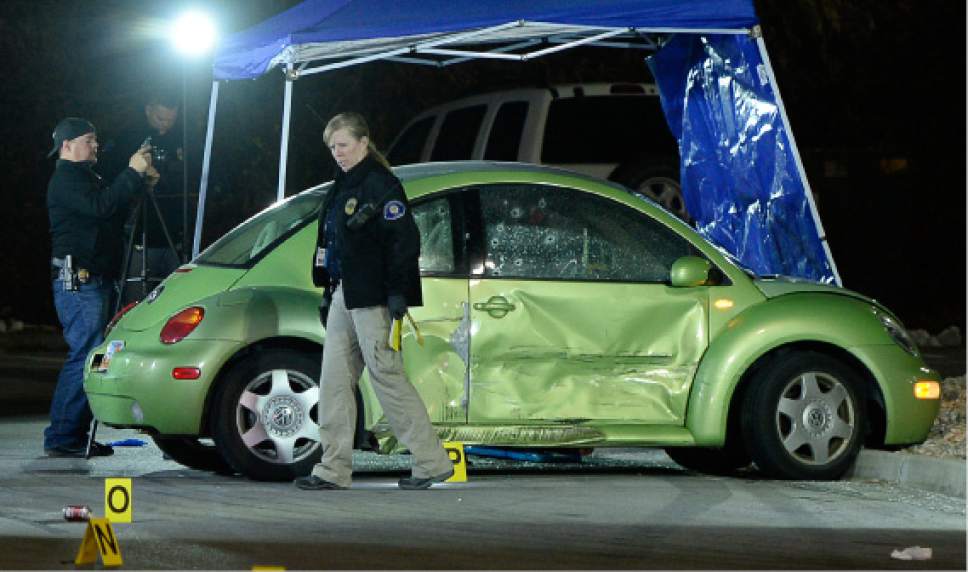

Sue Ann Sands, 39, was killed outside a busy shopping center after she met with Smith on Sunday, in American Fork, about 30 miles south of Salt Lake City, police said. Smith also died after a police chase erupted in gunfire, though police said it wasn't clear whether he killed himself or was killed by officers. He had been served with a protective order about two weeks before, after a beating that left her with bruises all over her face and body, Sands' mother told KUTV news.

Nichols said laws requiring people to prove they've given up their weapons after being served with restraining orders are important because access to a weapon makes it five times more likely that a domestic violence victim will be killed.

Others said making gun surrender a condition could turn the issue into a bargaining chip in divorce and domestic cases. Mitch Vilos, a Utah defense lawyer and firearms instructor who's written a book on self-defense, says women should arm themselves for protection.

"If the husband wants to kill his wife, it doesn't matter how many protective orders there are," he said.

Access to weapons is far from the only issue facing domestic violence victims in Utah, said Jenn Oxborrow, executive director of the Utah Domestic Coalition.

Nearly half of the state's homicides between 2000 and 2013 were related to domestic violence, but shelters remain underfunded, giving victims few places to go to escape abusers, she said.

Smith "may have fallen into some cracks in the system, but in Utah those cracks are enormous," she said. "Culturally, we don't realize how serious this is until something like this happens."